A surefire way to irritate me beyond reasonable measure is to not understand my (perhaps unreasonable) attachment to books. I love their weight and feel and their sense of occupancy, their reason for being–to attempt to communicate something beyond time and distance. I particularly love my art books. James Rosenquist by Judith Goldman is one of my favorites. The cover alone is irresistible (reminds me rather unsurprisingly of a great album cover) but her text is equally swoon worthy:

December 1983: “I’ve got an idea for a real zinger–women, flowers, and dead fish.” James Rosenquist has just returned from a meeting at New York’s Four Seasons Restaurant, where he discussed the mural they had recently commissioned from him. He is excited, physically animated. “Maybe the fish won’t be dead,” he continues, “but they’re going to have real slippery eyes. Slippery fish and beautiful women.”

“Did they understand it?” What I had meant to ask was if they liked it.

Rosenquist finds the question beside the point and not wanting to be impolite, steers the conversation in another direction. “Did I ever tell you about the time I was down in Florida visiting Bob Rauschenberg? We’d had dinner and a lot to drink. We were pretty swacked, and after dinner Bob showed me his new work. I looked for a while and told him I liked it, but I wasn’t sure I understood it. Bob started to laugh and laugh and was still laughing when he said, “Do you think I understand it?”

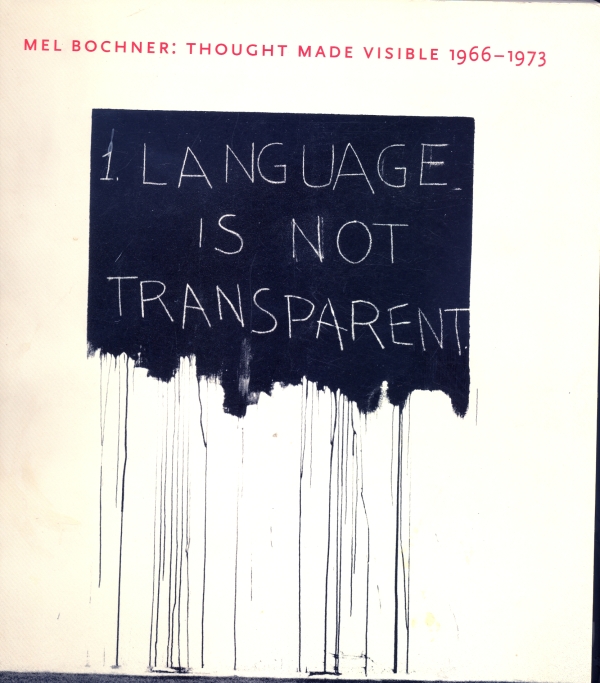

Another favorite is Mel Bochner: Thought Made Visible 1966–73, a catalogue published in conjunction with an exhibition at Yale University Art Gallery in 1995. I love this one primarily because I believe it changed my life. Really. I was 25 when I was introduced to Mel Bochner. I was working as a features reporter for a daily newspaper in Connecticut and by default had been assigned to provide arts coverage for the Sunday paper. I would drive around the state in a dying Mazda (it seemed to require oil replenishment every sixty miles) and write about artists, gallerists, and writers in the area (Cleve Gray, Robert Natkin, Rosamond Bernier, Jacques Kaplan) as well as regional exhibitions. Here is some of what I wrote about the Bochner exhibition:

Black-and-white, pen and ink, Bochner’s art includes everything from rough diagrams and preliminary sketches to typed letters and stamped envelopes. He defines art as measuring tape on a wall, floored newspaper painted blue, even stones placed on pieces of white paper. Rarely are Bochner’s works straight-forward. They require translation. They rely on finding a common language which is, of course, the trickiest art of all.

“Language is what keeps people apart and ideas from being understood,” says Bochner, a tall, slender man of model proportion with a sweep of thick, silver hair, and a tendency to wink frequently and smile occasionally. He is gentle and patient in the fluid, graceful way he moves his hands–more like a dancer, less like a salesman–when he speaks. “I’ve always been interested in the hidden conventions that govern life and art.”

I studied that catalogue like mad, trying to pin down his mental teasers. It was invigorating. His art made everything and anything possible–all forms of communication and miscommunication. It suddenly wasn’t something that I was failing to understand (and by it I mean those “hidden conventions” that had flummoxed me since at least adolescence); it was something that no one (not to be presumptuous or idealistic) completely understood even if they thought they did. Ultimately, the exercise of translation (and not just a single translation but repeated and often increasingly contorted translations) that Bochner’s art required opened an entire world of learning for me. I was no longer intimidated by not knowing; I was completely enthralled by it. Everything became about translation–from art and physics to mathematics and relationships. The world of knowing became one glorious invention of systems and practices that veiled the amazing and thrilling comfort of not knowing and perhaps, maybe and fleetingly, understanding just a little. Seriously and simply beautiful.

Caio Fernandes

/ January 9, 2010fantastic to have found this page !

sazky

/ January 17, 2010super post,wish all the best

Ava Gunter

/ January 18, 2011I loved reading your thoughts on the beauty of the mystery and the veil of language/systems of understanding. Great post.